|

| By Duncan.co (CC) |

Here's the latest news and notes from the authors here at Sci/Why:

Claire Eamer says: "Here’s my current fascination: An online interactive map, using data from NASA, that will show you the impact of sea level rise anywhere in the world. You can pick a level from 0 (current conditions) up to 9 metres in 1-metre increments, and then in larger increments up to +60 metres. It’s fascinating to see what even a 1-metre rise in sea level does to areas like the Netherlands or even Delta, BC – especially since that amount of sea level rise could happen within decades if climate change continues at the current pace. The site is at http://flood.firetree.net/."

Claire Eamer's latest science book is INSIDE YOUR INSIDES: A GUIDE TO THE MICROBES THAT CALL YOU HOME (Kids Can Press, 2016), and she has two more books coming out in a couple of months: WHAT A WASTE! WHERE DOES GARBAGE GO? (Annick Press) and a decidedly unscientific picture book, UNDERNEATH THE SIDEWALK (Scholastic Canada)

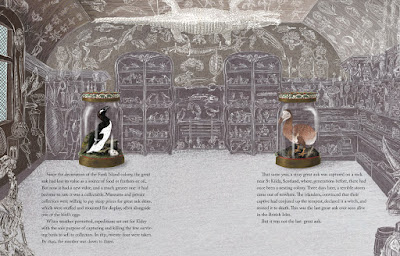

Helen Mason sent this: "My favourite web site is http://www.sciencemag.org/. Not only does the site have news, science papers, and podcasts, you can sign up for a regular newsletter that puts links to fascinating articles in your Inbox. My favourite book so far this year is The Tragic Tale of the Great Auk by Jan Thornhill. Thornhill's detailed artwork will attract many readers, as will the engrossing but unhappy tale. I particularly like the ghosts of the Great Auks on the final spread."

Helen Mason has authored 34 books, most of them for young readers. Crabtree will publish her A Refugee's Journey from Syria and A Refugee's Journey from Afghanistan in early 2017.

L. E. Carmichael says: "I highly recommend the adult-level science book Locust: The Devastating Rise and Mysterious Disappearance of the Insect that Shaped the American Frontier, by Jeffrey A. Lockwood. Part history, part ecological mystery, the book explains how an insect species that swarmed in the trillions went extinct in a few short decades. The events in the book happened over a century ago, but as we’re currently in the midst of a mass extinction event, the concepts are both contemporary and relevant. Plus, anyone who read Laura Ingalls Wilder’s On the Banks of Plum Creek as a kid will love learning more about the species that devastated her family’s farm."

L. E. Carmichael published 5 children’s science books in 2016: How Can We Reduce Agricultural Pollution?, The Science Behind Gymnastics, Discover Forensic Science, Innovations in Health, and Innovations in Entertainment. Her 21st book, Forensics in the Real World, releases in January. For more info, visit www.lecarmichael.ca.

Joan Marie Galat recently launched her newest astronomy book "literally" in a rocket at the Telus World of Science in Edmonton. Dot to Dot in the Sky, Stories of the Aurora reached 175 metres (nearly 600 feet)! She says, "If you want to launch a book in a rocket, you need to understand thrust, aerodynamics, and other forces. If you want to get your book back, you need to understand ejection and recovery systems! This NASA Model Rocket website is a good place to start."

As well as trying to get her book closer to space, Joan invited Canadian Astronaut, Dr. Dave Williams, to read Stories of the Aurora. He provided this back cover comment: "Having watched the aurora from space, I’ve known the unique thrill of seeing the lights swirl over the planet. Joan Marie Galat captures the science and remarkable folklore of the aurora in Stories of the Aurora, an inspirational collection of tales that makes the reader want to experience their beauty first hand." You can watch the rocket blast off and see book trailers on Joan's YouTube channel.

Try this from Jan Thornhill: "Here’s my website pick: the University of Florida’s Baldwin Library of Historical Children’s Literature has digitalized 6,000 old children’s books! These include 495 natural history books. Fabulous site to suck hours out of the universe!"

Jan Thornhill has two new books out this year: The Tragic Tale of the Great Auk (Groundwood) and I Am Josephine - and I Am a Living Thing (Owlkids). She hopes to have her website www.janthornhill.com updated this spring. She also continues to write about the really weird and interesting fungi she finds on her blog: https://weirdandwonderfulwildmushrooms.blogspot.ca

Helaine Becker says she's hoping to announce a new science book soon! And she does have a few books coming out this year. A science/math one: Lines, Bars, and Circles: How William Playfair Invented Graphs (picture book, KCP) and You Can Read! (picture book, Orca), which is "a pretty darn funny thumbs up to literacy." We'd expect nothing less!

Adrienne Montgomerie is totally geeky about knowing how things work, whether they're animals or machines or Earth or the universe! What she likes to hear most is "Can I read that when you're done writing?!" <scieditor.ca>

Adrienne sent this recommendation: "My favourite science book is Packing for Mars, by Mary Roach, because it is funny as well as informative, and it talks about a lot of the routine things that make up the bulk of life but that don't get talked about much. It's not all rocket telemetry and innovative fuels — sometimes it's just about how to brush your teeth."

Paula Johanson says, "This week, my favourite citizen science website is The Christmas Bird Count in Victoria: http://www.vicnhs.bc.ca/?page_id=1425. They even have a form that can be filled out by people at home watching the birds at a bird feeder. My plans for Boxing Day just got made. That's the day of the Christmas Bird Count for my town, Sooke.

In August, Paula's science book The Paleolithic Revolution from Rosen Publishing's series The First Humans and Early Civilizations was released. And also this fall release of two non-science books: The Spanish-American War, and Pierre Elliott Trudeau, a biography from Five Rivers Publishing's series on Canadian Prime Ministers. In January she has two more books coming out: Critical Perspectives on Vaccinations from Enslow Publishing, which is another science book (yay!), as well as Women Writers from the Enslow series Defying Convention: Women Who Changed The Rules.

And my turn: My book recommendation this year is Cattail Moonshine and Milkweed Medicine: The Curious Stories of 43 Amazing North American Native Plants by Tammi Hartung. Not only does this book give you the scientific names of these common plants, but she gives the details of their pre-contact and modern uses as medicine, food, and decor. And my favourite website comes from Claire Eamer's Sci/Why post "Over, Under, and On the Arctic Sea Ice." The Inuit Situ (Sea Ice) Atlas combines cutting-edge science with Inuit traditional knowledge on one of the most important environmental topics of our time.

And for my update: I'm just revamping my website at www.mariepowell.ca with the addition of 16 new books for young readers this fall. With another eight early- and middle-grade books coming out this fall, I should top 40 books in 2017.

What's your favourite science book or website this year? Enjoy these top picks from our Sci/Why authors bunker -- and please leave a comment!

Falalalala -- lala - la - LAAAA!

Posted by Marie Powell

.jpg)