|

|

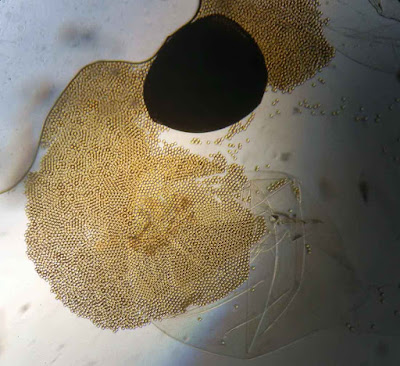

Photo by NASA Goddard Space Flight Center showing a C3-class solar flare that erupted from sunspot 1105 on

Sept. 8, 2010. Used under CCBY-2.0 license.

|

by Adrienne Montgomerie

“I

really like astronomy, but I can’t stay up that late,” I said to the astronomer

I met the other day.

“Lucky for me,” he said. “I do my astronomy during the daytime. Only optical astronomy really requires a night sky — and that's only

for ground-based telescopes!” Then Drew the astronomy PhD student at

Queen’s University went on to tell me about radio telescopy and telescopes out

in space.

Light is part of the EM spectrum, and so are X-rays and radio waves. Astronomers

can look for the X-rays and radio waves given off by stars and planets to learn

what they are made of and how they behave. That method works even when daylight

obscures the objects.

A couple years earlier, I met the team from RMC (the Royal Military

College) who study stars in daylight. Their specialty is the Sun!

Beginning

Daylight Astronomy

The easiest targets are our own Sun and Moon. You can watch the Moon

with your bare eyes and observe how its shape changes from crescent to fully

round and back to crescent. With a pair of binoculars, you can zoom in on the

craters and other features that show the Moon’s history of being hit by space

rocks. A telescope lets you see even more detail.

You can observe the how the Sun’s path across the sky changes with the

seasons. But you can learn more about the Sun itself.

It can damage your eyes to look straight at the Sun, but there are

filters that fit over a telescope to make observing the Sun safe. One really

fun time to observe the Sun is during a solar eclipse, but even with most of

the light blocked by the Moon, it’s still unsafe to look directly at the Sun. One

easy trick is to have a telescope project the image of the Sun onto a piece of

paper. With your back to the Sun, put paper below the telescope’s eye piece. You

can then look at the Sun on the paper.

Events

in the Daytime Sky

On August 21, 2017 there will be a total solar eclipse visible from coast to coast in the USA. It is only visible where the shadow meets

Earth, so not everyone will see it.

An eclipse is a great time to get a better look at the Sun’s corona. Because

the Moon blocks most of the Sun during an eclipse, it makes the remaining part

easier to see. The outer edge (corona) is where you can see great tongues of

fire exploding from the star (like in this picture). Those are called flares

and they can be as powerful as 1 billion megatons of TNT! Solar flares are what

send electromagnetic waves outward from the Sun. When they reach Earth, they

cause Northern Lights (and Southern Lights, too). When there’s a big solar

flare, you can watch for signs of it affecting Earth a few days later. It’s not

just pretty lights that solar flares cause. Sometimes that radiation interferes

with radio and power transmission here on Earth.

Lunar eclipses sometimes happen during the day, too. It’s not as

dramatic as a nighttime eclipse, but you can see Earth’s shadow take a bite out

of the Moon. You can see that without anything but your eyes.

To learn more about astronomy, check the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (RASC) and Sky News magazine.

Adrienne

Montgomerie is a science and education editor who helps publishers and

businesses develop training resources. She believes we

can make even the most complex ideas and procedures easy for learners to take

in, maybe even to master.