Title: It's About Time: Untangling Everything You Need to Know About Time

Author: Pascale Estellon

Publisher: Owl Kids

ISBN: 9781771470063

Book Source: review copy from publisher

I've published 10 science books for kids since 2012. Nine were "fact" books, dealing with straightforward, concrete information. The tenth is on the scientific method - a way of thinking - and my experience on that project showed me how much harder it is to write effectively about something so insubstantial and abstract.

Is there anything more abstract than time, the subject of Pascale Estellon's latest book?

Starting with one second and working up to one century, Estellon's done a marvellous job of taking the insubstantial and making it concrete. She relates each measure of time to a specific activity young children have already experienced, giving them a solid frame of reference. One second, for example, is the amount of time it takes to turn the page of the book; one hour is how long it takes to mix and bake a pound cake. The recipe for the cake is included, encouraging kids to tackle time in an interactive, hands-on way.

The book also includes questions, activities, and a clock kids can make and use while learning how to tell time. The design is extremely visual - Estellon's illustrations don't just add colour and life to the page, they are used to explain and help kids picture difficult concepts.

The only concept in the book I felt wasn't clearly explained is the Monday's Child rhyme included in the days of the week section - the heading asks kids "What day of the week are you?" without explaining that the rhyme relates to birth day. Unless kids are reading with an adult who's familiar with this rhyme and can explain, they may find this a bit confusing.

Altogether, however, It's About Time is cheerful, appealing, and very effective, and I heartily recommend it.

---

Review by L. E. Carmichael

14 Feb 2014

Penguin Enthusiasm

No, I'm not a penguin scientist -- though I am applying to join an Antarctic expedition as a writer-in-residence. But I did enjoy finding this pair of photos of a penguin who appears to be trying to join an expedition of his own:

What's the Name of That Bird?: A Sampling of Identification Guides (Part II)

by Jan Thornhill

|

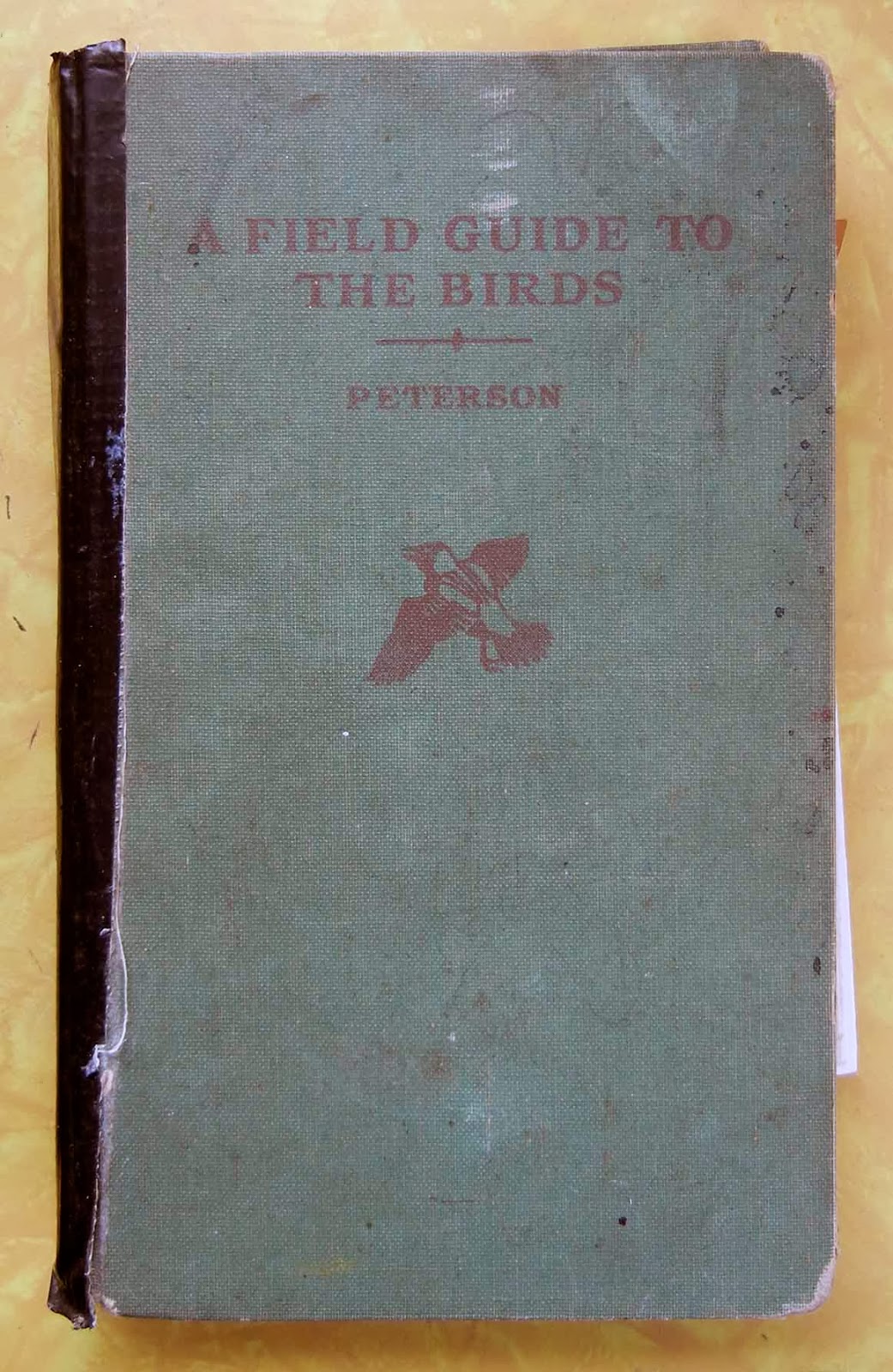

| My 1965 Peterson's Field Guide to Birds |

I blame my dad for nurturing my natural propensity to put

names to things. He was a walking encyclopedia and knew the names of all kinds of things—of rocks and minerals, of trees and plants, of clouds and bugs—and could easily explain the differences between, say, the flat needles of a hemlock tree and those of a balsam fir (hemlock shorter; fir with two light stripes on the

underside). He fell short, though, on the names of birds, and couldn’t differentiate between a Downy

Woodpecker and a Hairy one. Understanding that this was a flaw, he

bought the family a copy of Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds when I was ten.

It was spring thaw when he took me to the Humber River to

try it out. We shared the binoculars, but I was given the honour of being Keeper

of the Book. Breakup had just happened and the river was swollen and roiling,

carrying fast-moving ice floes towards Lake Ontario.

We Were on the River’s Edge When the Awful Thing Happened

|

| A Yellow-rumped, or Myrtle Warbler almost caused my dad's demise in 1965. (Dan Pancamo) |

In a family like mine, it was clear to me at a very young

age that books were important. I just didn’t know how important until that day.

My dad was no athlete. We didn’t play catch, and I never did

see him run. But when that book hit the water and started to float away, he leapt

into action. He skidded down the bank, and then—just like a super hero—he pounced

onto the nearest ice floe. It tilted precariously, but he maintained his

balance. Following the bobbing book, he leapt to the next floe. Then the next. He

kept going until the prize was within reach. Somehow he scooped it sopping from the water without falling in himself, then inelegantly danced from one floe

to another until he’d made it back to shore.

My dad had just risked his life for a book. A book! Powerful

moment.

The book, of course, was ruined. But no matter. He bought

another. Which I still have.

Sibley Guide to Birds

|

| This updated and improved Second Edition of the pocket version is due out next month. |

Remarkably, that Peterson guide held its position as my

birding bible for more than thirty years, and might have remained there if ornithologist

David Allen Sibley hadn’t decided to spend ten years hunkered down with

watercolours and brushes to paint the 6,600 images of 810 species found in the

Sibley Guide to Birds, first published by Knopf in 2000. With

multiple depictions showing alternate and juvenile plumages, flight patterns, and

comparative perching views, it’s a monumental and irreplaceable work. Though

the original edition is too cumbersome to be used comfortably in the field, pocket editions have been available for several years.

The Warbler Guide

One of the things the Sibley guide has been lauded for is its treatment of the more than fifty species of wood-warbler that nest in North America. These tiny jewels can be challenging to identify, partly because so many of them prefer to spend the bulk of their time flitting amongst the highest leaves of forest trees (hence a birder malady known as “Warbler Neck”), and partly because, by autumn, they’ve traded their fancy, and often brightly coloured breeding plumage for much drabber winter outfits. Making this latter, seasonal task of identification even more difficult is the addition of immature warblers wearing their own muted versions of adult markings. Peterson referred to these duller versions as, appropriately, “Confusing Fall Warblers.”

So what’s a warbler hunter to do? Well, Sibley’s is good,

but a new book, The Warbler Guide

(Princeton University Press, 2013), completely blows it out of the water. In

this unbelievably comprehensive book, Tom Stephenson and photographer Scott

Whittle tease warblers apart with a fine tooth comb—not literally, of course,

but with more than 1,000 photographs.

Each

species, (presented alphabetically by common name—yes!), is extensively explored with multiple

views, close-ups of distinctive characteristics, photographs of comparison

species, visual tips on aging and sexing, detailed range maps, and numerous captions that cover

behavioural traits. Each species is also given several

pages of sonograms to help with identification by song or call. “Quick Finder”

spreads show these little beauties from a variety of angles, fantastic resources that are

downloadable for free from Princeton University Press.

|

| The Underview Quick Finder from The Warbler Guide that will go a long way in reducing "Warbler Neck." |

Bird Feathers: A Guide to North American Species

But what if you see a warbler and before you can identify it it flits out of sight, leaving only a falling feather in its wake? Another book comes

to the rescue: S. David Scott and Casey McFarland’s Bird Feathers: A Guide to North American Species (Stackpole Books,

2010). The first part of the book has detailed information about avian

physiology, conservation, feather morphology, bird flight, tips on flight

feather identification, and an explanation of feather colour and iridescence.

|

| Red-tailed hawk feathers |

The bulk of the book, however, shows examples of each species’ right wing

feathers, all clearly photographed on neutral backgrounds, along with measurements

and range maps.

Whether you find a stray feather lying at the side of the road, or the fluffy, strewn remains of a predator's kill, this book, like all the others in this post, is a wonderful resource.

Whether you find a stray feather lying at the side of the road, or the fluffy, strewn remains of a predator's kill, this book, like all the others in this post, is a wonderful resource.

- Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America, Roger Tory Peterson, Lee Allen Peterson, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008, 544 pages. ISBN: 0618966145

- The Sibley Guide to Birds, Second Edition, David Allen Sibley, Knopf, 2014, 624 pages. ISBN: 030795790X

- The Warbler Guide, Tom Stephenson, Scott Whittle, Princeton University Press, 2013, 560 pages. ISBN: 0691154821

- Bird Feathers: A Guide to North American Species, S. David Scott, Casey McFarland, Stackpole Books, 2010, 400 pages. ISBN: 0811736180

7 Feb 2014

The 50 Greatest Inventions Since the Wheel? Maybe....

In the November 2013 issue of The Atlantic, the Editors present a list of their top 50 inventions since, well, the wheel.

A few years ago, I covered this same ground in my book What's the Big Idea? from Owlkids.

Needless to say, the choice presented in my book were not exactly the same as the ones the Atlantic came up with (and there are more of them). That's partly because I selected inventions based on what's most important to kids.

For example, there's the all-important needle.

The needle you say? Why would kids care about a needle?

Simple. The needle is what allowed our ancestors to survive the brutal cold of the Ice Age in Northern Europe etc. etc. They used it so they weren't totally reliant on furs for clothing. And think about it - if you drape furs around you, they can be a little drafty. You really need something to wear underneath them, something close to the skin that you can layer...

Underwear.

Without the needle, there'd be no underwear. And without underwear, we wouldn't have survived the freezy breezy.

So check out the Atlantic list of inventions for sure, but don't overlook, ahem, what's under-represented. Check out What's the Big Idea? for a real EYE-opener. (get it?)

PSST, while you're at it, you might what to check out my current book, Ode to Underwear! Yes, I have a "thing" for underthings!)

A few years ago, I covered this same ground in my book What's the Big Idea? from Owlkids.

Needless to say, the choice presented in my book were not exactly the same as the ones the Atlantic came up with (and there are more of them). That's partly because I selected inventions based on what's most important to kids.

For example, there's the all-important needle.

The needle you say? Why would kids care about a needle?

Simple. The needle is what allowed our ancestors to survive the brutal cold of the Ice Age in Northern Europe etc. etc. They used it so they weren't totally reliant on furs for clothing. And think about it - if you drape furs around you, they can be a little drafty. You really need something to wear underneath them, something close to the skin that you can layer...

Underwear.

Without the needle, there'd be no underwear. And without underwear, we wouldn't have survived the freezy breezy.

So check out the Atlantic list of inventions for sure, but don't overlook, ahem, what's under-represented. Check out What's the Big Idea? for a real EYE-opener. (get it?)

PSST, while you're at it, you might what to check out my current book, Ode to Underwear! Yes, I have a "thing" for underthings!)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)