by Kim Woolcock

Growing up, I was always the shortest person in my class. I was guaranteed to lose games of Keep Away. I could never reach the top shelf. And the basketball hoop seemed to be infinitely farther away from me than from other kids (OK, maybe there were other factors in my lack of baskets scored). But in sixth grade, my very tall friend gave me a sweatshirt that said, in glittery letters, Tiny but Tough, and that became my motto. So when my publisher sent me an image of a tardigrade (the poster children for Tiny but Tough):

|

|

Hypsibius dujardini Taken by: Willow Gabriel, Goldstein Lab http://tardigrades.bio.unc.edu/ |

and asked what I thought about doing a book on minibeasts, I jumped at the chance. I decided right away that it would be about not just minibeasts, but the superpowers of minibeasts. Because there are plenty of upsides to being tiny.

I read a giant stack of science papers while researching this book, and I learned about SO many fascinating creatures. One of my favourites is the water scavenger beetle (Regimbartia attenuata). These guys are just round black dots, a few millimeters long. They look completely unassuming. They don’t have any obvious defenses, and if a frog tries to eat them, well, it succeeds. They get swallowed. <gulp!>

But!

That is not the end of the story. Because after being swallowed, these beetles walk right out. That’s right—they get swallowed, and they don’t care. A few minutes to a few hours later, the beetles emerge ALIVE from the frog’s butt. It’s not clear whether the beetles hike out through the frog’s intestines, or whether they tickle the frog’s innards, maybe by wiggling their legs, encouraging it to send them speedily on their way.* Either way, these otherwise inconspicuous creatures are escape artists par excellence.

Along the way I learned that larvae of the horse mint tortoise beetle (Physonata unipunctata) defend themselves by carrying a poop umbrella with their butt. That Asian jewel beetles (Sternocera aequisignata) camouflage themselves with glitter. That the walnut-sized bobtail squid keeps glowing bacteria in its belly, to disguise itself as a moonbeam while it feeds in the nighttime ocean. And that because ogre-faced spiders listen with their legs, they can catch prey while blindfolded (and yes, scientists make tiny blindfolds for spiders).

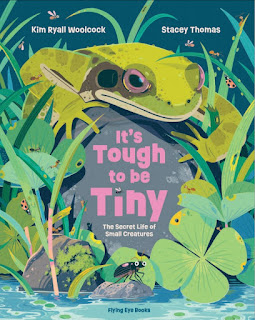

If you’d like to learn more about the amazing world of minibeasts, check out my book It’s Tough to be Tiny:The Secret Life of Small Creatures, illustrated by Stacey Thomas (Flying Eye Books, 2022). It’s all about the superpowers of small creatures, from springtails to cone snails, and how they stay safe, hunt for their lunch, or buddy up with bigger creatures for the benefit of both. It’s full of glitter and gross, because nature is both.

I’d like to know, which superpower would YOU choose?

* Wax-coated beetles didn’t make it out.

Resources:

K Kjernsmo, HM Whitney, NE Scott-Samuel, H Knowles, L Talas, and IC Cuthill. (2020) Iridescence as camouflage. Current Biology 30 (3): 551–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.12.013

M McFall-Ngai. (2008) Hawaiian bobtail squid. Current Biology 18(22):PR1-43-1044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.059

JA Stafstrom, Hebets EA. (2016) Nocturnal foraging enhanced by enlarged secondary eyes in a net-casting spider. Biology Letters 12: 20160152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0152

JA Stafstrom, G Menda, EI Nitzany, EA Hebets, and RR Hoy. (2020) Ogre-faced, net-casting spiders use auditory cues to detect airborne prey. Current Biology 30(24): P5033–5039.

S Sugiura. (2020) Active escape of prey from predator vent via the digestive tract. Current Biology. 30 (15): PR867–R868.

https://www.dailycamera.com/2010/07/22/jeff-mitton-tortoise-beetles-and-fecal-shields/

No comments:

Post a Comment