As it happens though, these little nubbins are crucial to our forests’ very SURVIVAL. How is this possible? Let’s dig a bit deeper. There are thousands of mushroom species, which are part of the Kingdom Fungi. Most live in the soil or on other living things like trees, and they feed mainly on dead matter. Unlike animals, they digest food outside their bodies, using chemicals to break down their meal before consuming it.

|

| Trees and mushrooms help each other. Guess what else they have in common? A fruit to plant ratio! |

Yes, some cause disease, but there are so many more helpful mushrooms than harmful ones. Our debt to our fungal friends goes back hundreds of millions of years, when life first started moving out of the oceans and onto land. Plants could not have made that leap without mushrooms first creeping onto the rocks and digesting them into nutrients (i.e. plant food, like phosphorus or magnesium). This allowed plants to move in, dry off, and, over millions of years, diversify into the incredible environments we enjoy today.

There are two main ways that forests STILL depend on mushrooms:

- Mushrooms decompose dead things. Think of all the leaves that fall and the plants and animals that die in the forest every year. Without decomposers, they would just lie there, eventually piling up enough to smother the forest itself. Luckily, fungi break it all down to nutrients that get recycled back into the forest system, supporting new life. Other critters like worms and beetles decompose dead things too, but — not to play favourites or anything — mushrooms do it the best.

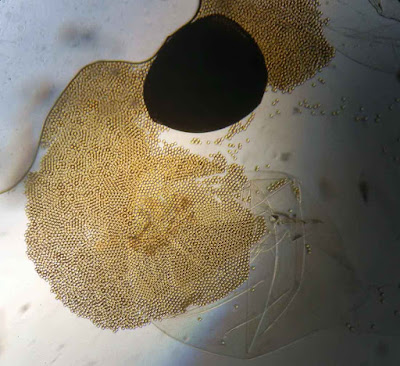

- Many mushrooms actually feed trees. That seems strange- what could fleshy little mushrooms have to offer towering trees? Here’s the thing: the mushrooms we see are only the reproductive bits attached to the main fungal body — called mycelium — which can be ENORMOUS! They’re similar to apples in this way, they make up just a small part of the entire apple tree.

The mycelium stays mostly out of sight — underground or inside trees — and is made up of thin, quickly-growing strands that look a bit like cobwebs. They can squeeze their way into the tiniest underground nooks and crannies, and are about 100 times better at getting water and nutrients from the soil than are the relatively shorter, stubbier tree roots.

So mushrooms gather water and nutrients for trees and deliver them right to their roots. Why so helpful? Trees give something back! Through photosynthesis, plants take carbon from the atmosphere to make carbohydrates (i.e. sugar), the main building block of plants. Most trees make extra: they give sugar to mushrooms, and mushrooms give water and nutrients to trees — a sweet deal!

These tree-fungal relationships are called mycorrhizae, and they benefit the vast majority of trees and other plants. Often neither the tree nor the mushroom could survive without the other! In harsher environments (like, let’s face it, Canada’s), forests really depend on mushrooms to stay healthy.

And who depends on forests? We all do! For clean air, biodiversity, climate regulation, food, lumber, and medicines to name a few. One thing that’s very clear — we have a lot to thank mushrooms for!