By Claire Eamer

I have a new book out -- and it's so disgusting that it once put my editor right off her dinner. I'm proud of that! (Sorry-not-sorry, Stacey.)

The book is called Extremely Gross Animals: Stinky, Slimy and Strange Animal Adaptations, and it's exactly what it claims to be -- a book about the animals that make you go "Ew!"

The thing is, once you get past the "Ew!" moment, these animals are fascinating. And adaptation itself is fascinating.

For example, when I think of mucus, I mostly think of snot and all the unpleasantness that goes with a bad cold or (currently) my over-reaction to pollen in the air. As I blow my nose for the tenth time in a morning, I am not feeling all that friendly about snot.

But when I learned about some of nature's snot-monsters, I started to change my mind. I'll be honest, I am just as likely as anyone to have a brief "Ew!" moment, but then.... Did you know that snot can be a primo defence mechanism? Or that snot can make a nice, safe place to sleep? Or a vehicle for travelling the world? Honestly, how can that not be fascinating?

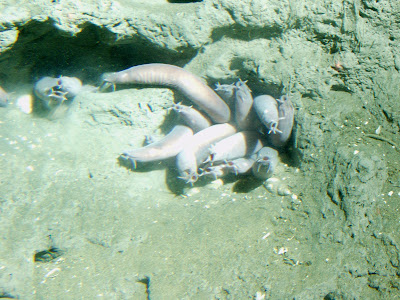

And it's all true. Consider the hagfish, a far-from-beautiful eel-like fish with a mouth out of nightmares.

|

| Pacific hagfish poking out of a hole 150 metres below the ocean surface. Credit: NOAA/CBNMS |

Then think about picking up a hagfish, or sharing a tank with it as this fellow does. When a hagfish is attacked by a predator -- or even by a television commentator having an "Ew!" moment -- it can produce enough slime (mucus, snot, whatever you fancy) by the bucketful, enough to clog the gills of any fish that fancies it for dinner. Watch here to see some high school students have their own "Ew!" moment at a hagfish research lab at the University of Guelph.

But what about that snotty but safe place to sleep? That's not hagfish, that's the parrotfish, a much prettier denizen of the world's oceans.

|

| A rainbow parrotfish. Photo credit: Paul Asman and Jill Lenoble |

A parrotfish spends its days pottering around coral reefs, eating algae that it has scraped off the coral with its bill-like mouth parts. At night, it sleeps safe and cozy in a cocoon of mucus freshly expelled from glands near its gills. Scientists aren't sure why. After all, you can't interview a parrotfish. However, the cocoon certainly keeps it safe from sharp encounters with coral, may protect it from parasites, and also would give it advance warning of any predator considering a midnight snack of parrotfish.

And the world traveller? Meet the violet sea snail, also called the purple bubble raft snail.

| |

| This violet sea snail washed ashore in Maui with its bubble raft intact. Public domain photo. |

As soon as it's born, the snail creates a raft of air bubbles enclosed in mucus to which its single foot is firmly stuck. The snail spends its life floating around the world's oceans upside-down, its foot attached to this mucus-and-bubble raft which keeps it safely at the water's surface. Both "Ew!" and "Awesome!"

And I haven't even begun to tell you what some animals can do with poop. Or puke. Or...well, you'll have to get the book for the rest of the grossness.

Enjoy!